Workforce Must be Prepared to Survive AI Wave

Published by The Star on 4 Dec 2025

by Thulasy Suppiah, Managing Partner

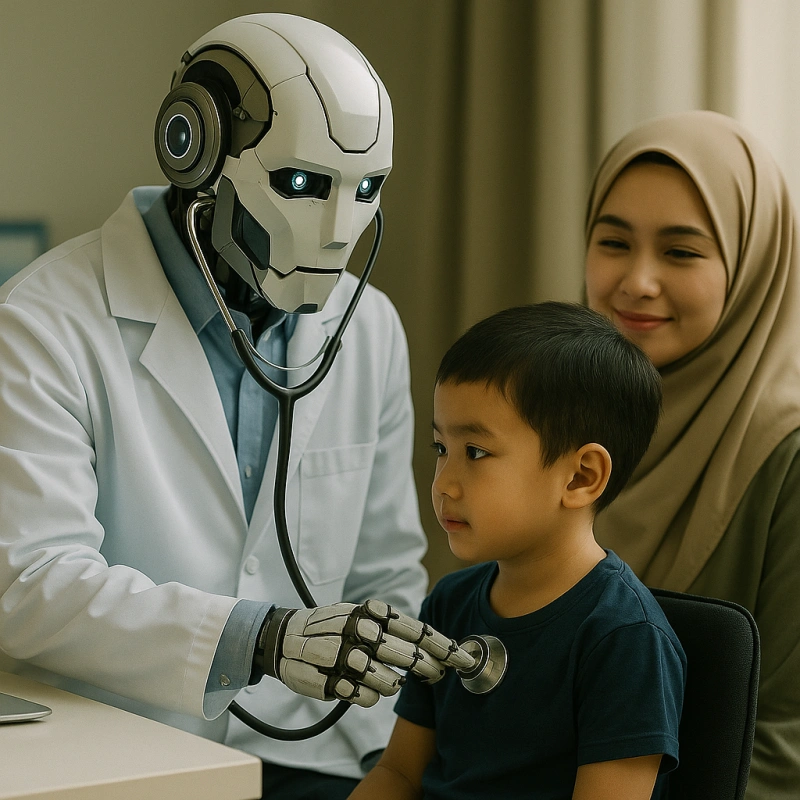

The recent announcement by HP Inc. to cut thousands of jobs globally as part of a pivot towards artificial intelligence is a stark, flashing warning light. It follows similar moves by tech giants like Amazon and Microsoft. This is no longer a distant theoretical disruption; it is a structural realignment of the global workforce happening in real-time. The question we must urgently ask is: Is Malaysia’s workforce prepared to pivot, or will we be left behind?

Locally, the data paints a sobering picture. According to TalentCorp’s 2024 Impact Study, approximately 620,000 jobs—18% of the total workforce in core sectors—are expected to be highly impacted by AI, digitalisation, and the green economy within the next three to five years. When we include medium-impact roles, that figure swells to 1.8 million employees. That is 53% of our workforce facing significant disruption.

While the government has measures in place, a critical gap remains in on-the-ground awareness. Are Malaysian companies thoroughly assessing which roles within their structures are at risk? More importantly, are employees aware that their daily tasks might soon be automated?

This is no longer just about competitiveness; it is about survivability. The speed of AI evolution is relentless. Take the creative and media industries, for example. With the advent of AI video generation tools like Google’s Gemini Veo and Grok’s Imagine, high-quality content can be produced in seconds. For our local media professionals, designers, and content creators, the question isn’t just “can I do it better?” but “is my role still necessary in its current form?”

Productivity is the promise of AI, but productivity without ethics is a liability. We witnessed this grim reality in April, when a teenager in Kulai was arrested for allegedly using AI to create deepfake pornography of schoolmates. This incident raises a terrifying question about our future talent pipeline: as these young digital natives transition into the workforce, do they possess the moral compass to use these powerful tools responsibly? A workforce that is technically literate but ethically bankrupt is a danger to any organisation and the community it serves.

Upskilling is no longer a corporate buzzword for talent retention; it is a necessity for future-proofing our economy. As indicated by the TalentCorp study, skills transferability will become the norm. The ability to pivot—to move from a role that AI displaces to a role that AI enhances—will be the defining trait of the successful Malaysian worker.

We cannot afford to be complacent. The layoffs at HP and other giants are not just business news; they are a preview of the new normal. AI is not waiting for us to be ready. Companies must move beyond basic digital literacy to deep AI literacy, auditing their workflows and preparing their human talent to work alongside machines. Employees must accept that the job they have today may not exist, or will look radically different, in three years.

The window for adaptation is closing fast. We must act with urgency to ensure our workforce is resilient, ethical, and adaptable enough to survive the AI wave, rather than be swept away by it.

© 2025 Suppiah & Partners. All rights reserved. The contents of this newsletter are intended for informational purposes only and do not constitute legal advice.